The boulders along the ridge are rounded, composed of diabase, which in my experience is associated with rare plant species that thrive in the particular kind of soil generated from the weathering of these rocks. The boulders were not deposited here by glaciers, but instead formed from molten upwellings from below. In Herrontown Woods and Autumn Hill Reservation there are numerous little abandoned quarries where some of the larger boulders were split into chunks and hauled away.

News from the preserves, parks and backyards of Princeton, NJ. The website aims to acquaint Princetonians with our shared natural heritage and the benefits of restoring native diversity and beauty to the many preserved lands in and around Princeton.

Sunday, March 27, 2022

Some Spring Sightings at Herrontown Woods

The boulders along the ridge are rounded, composed of diabase, which in my experience is associated with rare plant species that thrive in the particular kind of soil generated from the weathering of these rocks. The boulders were not deposited here by glaciers, but instead formed from molten upwellings from below. In Herrontown Woods and Autumn Hill Reservation there are numerous little abandoned quarries where some of the larger boulders were split into chunks and hauled away.

Saturday, March 12, 2022

A Night-time Visit to a Vernal Pool Along the Princeton Ridge

Here are a couple wood frogs in what's called "amplexus," with the smaller male holding onto the pinkish female. It looks all very ordered and peaceful, but when we visited a vernal pool in Herrontown Woods a week ago, the competition between males for females was intense, to the point of imperiling the females.In this photo, by Mark Manning, the tussle looks pretty benign.

Lincoln Hollister Leads a Geology Walk (POSTPONED)

The walk is at 1pm. A limited number of spots are available. Click here to sign up.

Also at Herrontown Woods this Sunday, and just about every Sunday of the year, volunteers gather from around 10:30 to 1pm to work in the Barden and elsewhere in Herrontown Woods, weeding, cutting down invasive species, and improving trails.

On first Sunday's of the month, from 10am-noon, FOHW hosts May's Barden Cafe, serving coffee, tea, and pastries in the tradition of Elizabeth "May" and Oswald Veblen, who donated Herrontown Woods back in 1957.

Saturday, February 26, 2022

Bird and Plant Walk at Herrontown Woods this Sunday

Join us for a bird and plant walk at Herrontown Woods this weekend, Sunday morning at 9, beginning at the main parking lot off Snowden. We'll have multiple walk leaders with expertise ranging from botany to birds to amphibians. Princeton natives John L Clark and Fairfax Hutter will be joined by naturalist and Hopewell teacher Mark Manning and myself. If lots of people show up, we can always split into multiple groups and head different directions.

Fairfax offered up some thoughts on what birds we may see and hear:My guess is that the birds we could find would be White-throated Sparrows, Song Sparrows, White-breasted Nuthatches, Juncos, N. Cardinals, Blue Jays, Titmice and Chickadees, Vultures, and probably easiest to spot would be (in this order): Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Pileated Woodpecker (yay!), and maybe a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (I hear them first).I like the positive reference to poison ivy berries there. It's not a favorite plant where it grows on the ground, but as it ascends a tree it gains some positive traits, producing important berries for the birds and turning bright colors in the fall.

I’m hoping we might see and/or hear a Brown Creeper, they’re really neat birds. This is the time of year for them and I’ve seen them in HW while looking for amphibians. We could also get some Yellow-rumped Warblers, esp. if there are any poison ivy berries left.

Thanks to the Princeton Public Library for helping get the word out about this event, which is in addition to our usual Sunday morning workdays that start around 10:30.

Friday, February 25, 2022

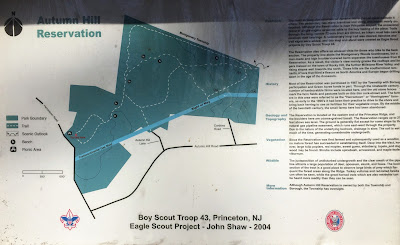

Autumn Hill Reservation--Past and Present

An early presence out Autumn Hill way, east and south of the present day preserve, was Camp Tamarack, the 30 acre Girls Scout camping ground that dates back to 1948. Remnants of a foundation and outhouse can still be found by following an old abandoned trail down from the end of Autumn Hill Road--a deadend street that was built as part of a subdivision in 1956. Girlscouts would camp there on weekends, sometimes combining the camping with sailing on Carnegie Lake.

A 1966 article announces obliquely that Township Open Space Commission "has obtained use of the Autumn Hill Reservation," and in 1969 the preserve is described as "new", with a parking lot but trails not fully laid out. The sign on the kiosk says that most of the land was acquired in 1967, with funding from township, borough, and the state's Green Acres fund."Autumn Hill" is the newest of the Open Space lands in terms of a good loop trail you can follow. The trail was built by YMCA Rangers. Picnicking is invited in Autumn Hill, too, and later this spring, there will be picnic tables. Right now, there is drinking water and you can bring your own picnic lunch.

In 1984, a big battle raged to fend off a proposed road, Route 92, that would have destroyed large swaths of open space, including part of Autumn Hill Reservation.

Fast forward to 1995, when local arborist Bob Wells proposed to officially adopt Autumn Hill Reservation. Bob was renting the nearby Veblen House from the county at the time.

Committee accepted an offer from Robert Wells that his tree and landscape firm adopt the park at Autumn Hill Reservation off Herrontown Road. Mr. Wells, chair of the Township Shade Tree commission and a Herrontown Road resident, has performed extensive tree and trail maintenance in the park on a volunteer basis over the past several years. He also supervised the creation of one trail that was an Eagle Scout project. He now proposes to reestablish the picnic area off the parking lot, rebuild the frost-free water spigot and erect an additional foot-bridge. He also plans to install tree identification signs and a trail map and do general maintenance to the trails and path system. In accepting the offer, Township Committee signaled it was launching an "adopt-a-park" program to enable other businesses and individuals to volunteer their services for Township parks.

There's been an increase in interest in Autumn Hill recently, particularly from people living on the other side of the ridge in Montgomery who would like a better connection to the preserve from that side. Though we've done some small reroutes of trails onto drier ground, there is more we hope to do this year, laying boardwalk and shifting some trails to drier ground.

Winter is a good time to look for better routes for trails. Andrew Thornton and I recently noticed a potential improvement that would run along the edge of a stone wall currently hidden by densely growing honeysuckle, winged euonymus, Asian photinia, barberry, and privet. The nonnative shrubs flourish because deer and other wildlife don't eat them. I made some headway one afternoon, cutting through the thicket with loppers and a saw, constantly dodging the thorns of multiflora rose. Who's to say what the dominant motivation is. Love of a good trail? A desire to leave the world a better place than one found it? The satisfaction of work where progress is clear? A stewardship ethic engrained from youth? One strong motivation is the standing water that makes the current trail route nearly impassable this time of year. Rerouting the trail along higher ground, next to a rock wall, will give us a trail that's both drier and more interesting. Win-wins help to spur one on.

Looking back through time, it can be heartening to see how people in the past stepped up to take care of public lands, just as we do now. It can also be unsettling, though, to see that periods of care do not always last, and can be followed by periods when trails slowly return to thicket, awaiting the next inspired steward to come along. What makes us think current efforts will be any different? That "adopt a park" program started in 1995 was well-intentioned, but the groups that stuck with it after the first flush of interest are few.

During my Durham days, I started a program in which interested neighbors could adopt 20 feet of a paved bike trail that went through a nature preserve. The aim was for each family or individual to gain a sense of ownership of a small section of trailside vegetation, planting native plants and weeding occasionally, until the entire length of trail would be a verdant showcase for sedges, rushes and wildflowers. There was early interest, but most people didn't stick with it. What I learned is how few people are hardwired to garden, and even fewer hardwired to garden in a public space.

Back in 1973, recycling was in a similar "heroic" stage, with a few dedicated volunteers trying to divert newspapers, bottles and tin cans from the waste stream. Like many municipalities across the country, Princeton was grappling with how to "get recycling out of the garage and volunteer stage and into the solid waste volume reduction and resource recovery stage on a long term regional basis." I was part of that 70's era volunteer recycling stage as well, standing on a flatbed truck as we drove through a neighborhood, stacking homeowners' bundled newspapers on the truck, and crushing glass--brown, green, and clear--in oil drums, as part of a pilot curbside recycling program in Ann Arbor, MI. Curbside recycling ultimately became institutionalized, but stewardship of open space is still in the "catch as catch can" volunteer stage.

Postscript: There's another question that lingers from this dive into history: Where is that water spigot from which drinking water once flowed in Autumn Hill Reservation?

PostPostscript: Didn't take long to find the old water spigot, just a few feet away from the parking lot.Friday, February 04, 2022

May's Barden Cafe at Herrontown Woods -- Sunday, Feb. 6, 10am to noon

May's Barden Cafe has become a popular gathering on first Sunday's of the month, with coffee and baked goods served amidst the plantings and winding trails of the Botanical ARt garDEN, just up from the main parking lot for Herrontown Woods, off Snowden.

Nicole Bergman has been teaming up with Joanna Poniz to host the Cafe, with coffee from Small World, and baked goods contributed by friends."May" was the nickname for Elizabeth Veblen. She and her husband Oswald donated Herrontown Woods long ago, and also started the tradition of afternoon tea at the Institute for Advanced Study.

The road down to Herrontown Woods is directly across from the main entryway to Smoyer Park. 600 Snowden Lane is now the official address for the parking lot. If the parking lot fills up, you can swing over to 452 Herrontown Road and park in the Veblen House driveway, then take the orange trail down to the Barden.

Princeton ECHO Takes Herrontown Woods Downtown

Through the month of January, a scene from Herrontown Woods could be seen adorning the cover of the Princeton ECHO in downtown businesses and along Nassau Street. The aim of bringing Herrontown Woods downtown in a feature article, according to author Patricia A. Taylor, was to draw people out into Princeton's nature preserves in the winter.

Adventuring out for a nature walk in winter has its advantages. The woods is filled with light and vistas, the frozen ground makes for good footing, and streams that may slow to a trickle in summer make rich, relaxing sounds with their winter flow.In the article, "History and helpful hands in Herrontown Woods," Patricia tells of taking her grandkids to the preserve and having great fun exploring the trails and the Barden. The article explores the history of the preserve and our Friends of Herrontown Woods nonprofit. She also tells the story of the dugout canoe in the Barden, and how it was originally constructed for an Odyssey project at Princeton High School.

For those who may have missed the paper edition, the article continues to live online.

Monday, January 24, 2022

Banana Palms and Lime Trees in Princeton

There's a house along Lake Drive in Princeton that has a special garden. Soon, the house and garden will be bulldozed and replaced, if history is guide, with sterile lawn and generic house, as the destructive side of prosperity has its way with the landscape. It was an estate sale, and before it changed hands I was invited to help myself to whatever was left in the house's garage and yard.

One of the more surprising finds was a grove of banana palms 10-15 feet high. Each year its loving owner would cut the palms down to the ground and mulch the roots heavily with leaves to protect them from the winter weather. And each spring the banana palms would rise to cast a tropical spell on her garden.and bears perfectly usable limes. They usually get a handful of fruit, but last year got 40.

Sunday, January 16, 2022

Witnessing a Cotton Plant

Saturday, January 08, 2022

A Mystery Tree Grows in Princeton

New growth is distinctive.

Fruits are red, and scarce considering all the blooms.

He referred to the texts by Dirr and Easton, particularly a quote from Easton: “Chokeberries remind us that scientific taxonomy is only the least imperfect of the tools that we have fashioned to help us classify and understand organisms”I have no doubt that this is one of the Aronias:

- Rosaceae flower

- Alternate, simple, elliptic leaf that comes to an acuminate point.

- Small, even, serrated margins

- Secondary veins disintegrate before reaching the margins

Thursday, December 30, 2021

Native Chestnuts in Princeton--the Next Generation

Many of us have lived our whole lives without seeing a mature native American chestnut tree. An excellent NY Times Magazine article described it as a true gift of nature, the perfect tree, growing straight and tall, with rot-resistant wood, and bearing nuts that were easily gathered and eaten, sustaining wildlife and people alike. My first encounter with the American chestnut was the sight of their fallen trunks in a Massachusetts forest, 70 years after the fungus that causes chestnut blight was discovered in NY city in 1904. The massive trunks I saw, lying on a slope in the shade of young white pine, were among the billions that the accidentally imported fungus would ultimately kill in the U.S. Since the roots survive the fungus, there was still a living community of underground chestnut trees beneath our feet in that Massachusetts forest. One of the roots had sent up a sprout about twenty feet tall--promising, one would like to think, but its slim trunk was already ringed by the fungus, its fate sealed before it could bear nuts.

One of the projects I'm involved in is reintroducing native chestnuts to Princeton. The initiative began in 2009 with an email from Bill Sachs, a Princetonian with considerable expertise when it comes to nut-bearing trees. Bill reported that Sandra Anagnostakis, "one of (if not the) world’s leading experts on the pathology of American chestnut," had agreed to supply us with disease-resistant, hybrid American chestnut trees. Sandra's efforts to breed resistant native chestnuts at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station over many decades was apparently unconnected to the American Chestnut Foundation. The trees were 15/16th native, and Bill with occasional help from me and others proceeded to plant them at the Princeton Battlefield, Harrison Street Park, the Textile Research Institute, Mountain Lakes and Herrontown Woods.

Some fared better than others. Many, despite having been bred for resistance, nonetheless struggled with the blight that had laid the mighty tree low a century ago. This fall, however, paralleling our work to bring back native butternuts, one of the chestnut trees has borne fertile seeds.

Bill made repeat visits to the tree to collect the nuts as they ripened. The deer likely got many, but he managed to gather quite a few, some of which he encouraged me to cold stratify. Stratification has always been an intimidating concept for me, suggesting sophisticated manipulation to get a seed to germinate, but in this case it turned out to be not much more than stuffing some seeds in a bag of moist peat moss and leaving it in the back of the refrigerator for awhile.