News from the preserves, parks and backyards of Princeton, NJ. The website aims to acquaint Princetonians with our shared natural heritage and the benefits of restoring native diversity and beauty to the many preserved lands in and around Princeton.

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query pollarding. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query pollarding. Sort by date Show all posts

Monday, February 24, 2014

Pollarding in Princeton

Hidden in Princeton's stark winter canopy are subtle signs of a quiet revolution, or at least something decidedly French. Some may view this tree profile as deeply troubling, while others may see a useful approach to solving several problems Princeton and other NJ towns are currently confronting. Halfway down the trees, you'll see a sudden thickening of the trunk. That's where the tree was given a buzz cut, maybe ten years ago. New shoots then sprouted from the cut tips.

This practice is called pollarding, defined as "a pruning system in which the upper branches of a tree are removed, promoting a dense head of foliage and branches."

When I've mentioned this practice to local arborists, the response has typically been negative, with talk of increased risk of disease, and structural weakness. It's true that I've seen a couple radically pruned trees send out a few feeble shoots the next year, and then die, leaving the likes of a telephone pole in the yard. But results depend on technique, timing, and species of tree. In Europe, where pollarding has for centuries been a clever means of harvesting fuel and forage from trees without cutting them down, the pollarded trees are said to actually live longer than untrimmed trees. (Coppicing, a related practice of periodic heavy pruning once commonly used in agriculture, allows repeated harvest from a tree root that can live for 1000 years.)

My first reaction years ago, seeing a grove of trees getting hacked back in a city park in Madrid, was one of disdain and disgust. How could anyone choose to interfere with a tree's yearning for the sky? There's pleasure in tracing a massive tree's natural ramification, up and up to the top of the canopy. A tree, like a river, should run free.

Though a natural growth form works in most situations, I began to question my dismissive attitude towards pollarding about 15 years ago, when hurricane winds flattened many of the oaks in the NC town where I was living at the time. My view of oaks as being deeply rooted and timeless also came crashing down that day. Though most of the giant trees displayed an uncanny knack for missing cars and houses on the way down, I was made suddenly aware that we essentially accommodate wild trees in our midst, reaping all the benefits and potential downsides thereof. One of the willow oaks that survived the hurricane winds unscathed had been pruned years prior, pollard-style, causing the crown to be populated by many narrow, flexible branches, none of which was large enough to damage a house if it broke off. For years I had looked at that tree's altered growth form with dismay, yet there it was after the storm, a healthy survivor continuing to provide shade with minimal threat of doing harm to the house it was shading.

With Hurricane Sandy and other highly destructive storms sweeping through Princeton in recent years, some homeowners are torn between all the benefits trees can bring in the urban landscape, and the potential downsides of having all that weight poised above the roof. Personally, I have our trees looked at periodically to make sure they're healthy, and accept the risk. But if there's a way to manage trees so that one gets the benefits while minimizing the hazard, that could lead more homeowners to keep the trees they have and plant more.

Now, before buds open, is the time to check out what's being done around town. This photo and the closeup that follows shows evidence of trimming back on a tree that beautifully shades the house in the summer.

Perhaps the tree lost some high branches from high winds, or maybe it was an intentional effort to minimize any additional height.

Once one opens up to the idea of manipulating tree growth, a whole new range of possibilities opens up. Fruit trees of course, like this one in an Italian neighbor's backyard, greatly benefit from regular pruning. But a related approaches can be used for trees grown for any purpose, be it firewood, nuts, forage or shade. Pollarding and coppicing (a related practice) are used particularly in permaculture to maximize production in small spaces. If Princeton is serious about growing its food and fuel locally, a more engaged approach to managing trees will be a big component. Interestingly, these practices are also a means of managing lands for biodiversity, by creating more varied habitat.

These periodic prunings can also have benefits for both soil and atmosphere, by increasing soil organic matter and sequestering carbon. To grow roots, a tree utilizes carbon dioxide from the air to manufacture the building blocks of its structure. By growing roots, trees essentially transfer carbon from the air down into the soil. Each time a tree is pruned, a portion of its root system will die back to rebalance the ratio of roots to limbs. The roots that die back provide a legacy of carbon-based organic matter in the soil and channels for rainwater to seep into. New roots then grow as the canopy recovers, sequestering additional atmospheric carbon underground. More on the many benefits of coppicing at this link.

How these practices would fit into Princeton's goals for shade, food and sustainability are worth considering. The blanket condemnation of pollarding found in pruning manuals doesn't fit with examples past and present of its usefulness. If techniques specific to New Jersey's trees can be developed and accepted by arborists, this approach to pruning could add to the ways tree growth can be controlled to better coexist with homes and solar panels, and thereby increase the number of trees in town.

Here are some examples of pollarding in Paris.

My writeup on another transformative agricultural practice with big consequences for sustainability, the growing of the currently banned crop called hemp, can be found at this link.

Thursday, October 17, 2019

"Sprout Lands" -- Restoring a More Active Role for People in Nature

Princeton was offered a much different view this past Sunday, during a talk at the Princeton Public Library by William Bryant Logan, author of Sprout Lands: Tending the Endless Gift of Trees. His visit was co-sponsored by Marquand Park and initiated by arborist Bob Wells. Logan is an arborist, not an activist, yet his book seeks to raise awareness of two nearly lost words--coppicing and pollarding--and an active way of interacting with trees that for millenia benefitted not only people but nature itself. Nature, it turns out, has talents that can be trained much like our own.

Coppicing involves periodically cutting a tree to the ground, which may sound unkind, but if done in the right way with the right kinds of tree can result in numerous vigorous sprouts that produce slender stems for basketmaking, poles for fences, growing mushrooms or making charcoal, nuts for people and forage for livestock. Pollarding also involves periodic cutting of the tree, but farther up on the trunk, so that the resprouts are beyond the reach of browsing animals. Though such aggressive pruning may sound harmful, Logan describes this ancient practice as a kind of renewal that removes accumulated problems and allows a tree to start over again. It's not uncommon for a coppiced or pollarded tree to live 1000 years or more.

Most of us who pay attention to trees have been vaguely aware of these techniques. For an American, it can come as a shock to see them on display in the streets and countrysides of Europe. My first doubts about our entrenched let-grow approach to urban trees came in the 1990s after moving to North Carolina, where I soon witnessed the devastation wrought by Hurricane Fran. A pollarded oak survived the winds, while many of its untrimmed brethren came crashing down. Years later, on a gray, wintry day in 2014, prompted by the silhouettes of some aggressively pruned trees in my Princeton neighborhood, I read up some and posted on this blog about how pollarding in Princeton could make our neighborhoods safer, allow us to better integrate trees and rooftop solar panels, and use trees to more effectively absorb excess atmospheric carbon and inject it into the ground.

The revelation for Bill Logan, who is on the faculty at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, also began on a wintry day, while standing in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where his company had been given the responsibility of caring for a grove of pollarded London plane trees. Realizing the limits of his knowledge on the subject, he began what would become a journey back in time and around the world to recover the techniques and tell the story of a nearly lost art of cultivation central to past civilizations and relevant to our own. The eloquently narrated journey, enlivened by a clear love of culture and horticulture, along with vivid memories of encounters with trees in his youth, takes us from England to Spain, Norway, Japan, and ultimately to Logan's homeland in California, where Native Americans would use fire to stimulate the abundant sprouts and acorns that allowed them not only to survive but to prosper.

In each case, coppicing and pollarding served as a foundation for cultures that interacted with nature not in the "impose and extract" manner that has dominated the industrial age, but in an exchange in which both people and nature could flourish. Coppiced hillsides were harvested in rotation on fifteen year cycles. Each fresh harvest allowed sunlight to reach the ground, awakening dormant seeds and spurring a surge in vegetation that transitioned in succeeding years from herbaceous growth to brambles and then back to shade as the coppiced trees regrew. Each stage of succession supported its own cohort of plants and animals--a diversity twice that of an unmanaged forest.

It is Logan's loving description of the coppicing common in Japan before World War II that is the most inspiring and also the most heartrending, given all that was lost in the post-war modernization and urban expansion. Coppiced hillsides held the soil and absorbed the rainfall that in turn fed springs critical for growing rice in the valleys. These, Logan realized, were the landscapes described in the classical Japanese poetry he had encountered as a young man in college.

There was a time, then, when nature around the world was intensely managed, and richer for it. Multiple times, Logan describes how this management would sometimes go awry, and people would need to adjust their techniques. Through mistakes, people learned how to live with the nature they depended upon. My speculation is that Native Americans, new to this continent, at first erred in their overharvest of megafauna, then took lessons about co-existence from the resulting extinctions. Our own immigrated civilization has in turn made far greater mistakes, and has resisted learning from them, with heedless extraction countered by hands-off preservation, neither of which serve nature's needs, nor ultimately our own.

Though Logan does not overtly advocate, his research and writings point to the possibility of re-integrating people with nature. Restoring nature could include restoring the positive role our economic needs once played within it. With knowledge and a caretaker''s sensibility, we would shift from being antagonists or passive protectors to active protagonists--allies and beneficiaries of a balanced, diverse and prospering nature.

There are, of course, challenges. Past neglect leaves a legacy that is hard to overcome. One audience member pointed out how invasive species could derail the once rich succession of native species that coppicing had in previous centuries produced. Logan describes the challenges of renovating a pollarded tree whose limbs have been allowed to overgrow. The long eclipse of these techniques is reminiscent of the long suppression of beneficial fire in America's forests and prairies, beginning with the ban in 1911 that led to dangerous fuel buildups in our forests--the explosive conditions that feed the mega-fires we see today. Like people, a neglected and abused nature cannot simply be reset to a previous era.

Personally, I view Logan's research as relevant to our management of Princeton's open space, and in particular the land surrounding the Veblen House and cottage at Herrontown Woods. The techniques he witnessed in western Norway, a combination of grasslands and pollarding that he described as "one of the most intelligent systems of farming anywhere in the world," suggest it's worth exploring what Veblen's ancestors in south-central Norway were doing on their farms in the Vadres valley. Many native species nurtured by Native Americans--blueberries, shadbush, Blackhaw Viburnum, hazelnut--grow in Herrontown Woods, their fruiting suppressed by deep shade. A meaningful task, already begun, would seem to be to manage open areas where these understory species can prosper.

After the talk, Bob Wells and I gave the author a tour of the Veblen House site, where plantings of pawpaws, hazelnuts, and butternuts fit nicely with the theme of his talk. When I took the opportunity to ask Bill what, beyond the ban on forest fires in 1911, shifted us away from an active management of trees, he offered a surprise answer. He speculated that a major shift came in the mid-19th century, when the saw became cheaper than the axe. Since trees could then be easily turned into boards, sprouts became less useful, and trees were allowed to grow up. The proud culture of the axe faded before the advance of the saw. Suddenly, as we walked the wooded corridor between the Veblen House and Cottage, Veblen's love of wood and the chopping thereof took on a deeper historical meaning.

The history of coppicing and pollarding, beautifully told in Sprout Lands, suggests that the way forward includes recovering much that has been left behind. In describing past eras, Bill Logan also describes living remnants in Europe and restoration of coppiced landscapes in Japan. These point to a way to prosper by working more actively with and within nature.

Monday, October 03, 2022

The Jazz Naturalist Travels to England

Botanical and musical interests merged recently, while touring England with a latin/jazz ensemble I've been musical director of for almost 40 years, called the Lunar Octet. It was a whirlwind tour, with seven gigs in five days. Along the way, I was able to catch glimpses of nature in the British Isles.

One of our hosts, in Tunbridge Wells, has a delightful garden. The city is located in Kent, which is a county south of London. England as a country has no states, but rather lots of counties, like Hampshire, Yorkshire, and Devon, which seems to have lost its shire. Homes have addresses in England, but they are also sometimes given names. Our host lives in the Sandstone House. Are all english gardens like this? I'd be fine with it if so. Sheep graze peacefully in the front yard. Had never seen baby sheep grazing before. They're doing a great job.

Pink flamingoes are an indicator species for quirky habitat. Real flamingoes can be found in Africa and America. I once saw flocks of them at watering holes at the base of the Andes in the Patagonian desert in Argentina. Plastic pink flamingoes (Phoenicopterus plasticus) are a northern species, reportedly native to Massachusetts.

One of our hosts, in Tunbridge Wells, has a delightful garden. The city is located in Kent, which is a county south of London. England as a country has no states, but rather lots of counties, like Hampshire, Yorkshire, and Devon, which seems to have lost its shire. Homes have addresses in England, but they are also sometimes given names. Our host lives in the Sandstone House. Are all english gardens like this? I'd be fine with it if so. Sheep graze peacefully in the front yard. Had never seen baby sheep grazing before. They're doing a great job.

Pink flamingoes are an indicator species for quirky habitat. Real flamingoes can be found in Africa and America. I once saw flocks of them at watering holes at the base of the Andes in the Patagonian desert in Argentina. Plastic pink flamingoes (Phoenicopterus plasticus) are a northern species, reportedly native to Massachusetts.

The nylon strings draped over the front yard water feature looked at first like a sculpture, but may also be an elegant deterrent of whatever local water bird might be tempted to fly in and gobble up the fish.

There was a very scary guard dog, fortunately leashed.

And a guard bird kept an eye on us. People underestimate guard birds at their peril.

There was a sheep patrolling the deck, looking like a character out of Wallace and Gromit. Very high security.

The garden deals with the death of trees in an interesting way. People tend to eliminate all signs of death from their gardens, but our hosts see demise as an opportunity. What's this?, you might ask.

I did ask, and was told that it's a thumb. That's a very positive thing to do with a dead tree trunk.

And that split trunk in the distance, instead of cutting it down,

they added a rope and called it a sling-shot.

If you've been steeped in the American ethic that trees should be allowed to grow naturally, the European treatment of trees can seem at first brutal. This eucalyptus, native to Australia, is lucky to have any limbs. Radical pruning is a means of controlling size, and is reminiscent of how grape vines are pruned back each year to not much more than a post sticking out of the ground. New growth sprouts from the tips. Pollarding is a fascinating technique with a long history, and some examples, intentional or not, can be found in Princeton.

Even more extreme pruning leaves just the trunk, as can be seen in this photo taken on the fly. It would be interesting to see how the trees respond to such extreme treatment.

There was a forest nearby that I didn't have time to explore, but the description sounds appealing.

Most jazz musicians, leaving the gig, would not have noticed the teasel growing in the little butterfly garden that was trying mightily to do its part to counter 50 years of decline in butterflies and moths in Great Britain. Apparently native to England, teasel is a plant with a striking form that unfortunately has become highly invasive in the midwestern U.S., forming thick stands along highways. It probably will become problematic in NJ over time. Typically there's a lack of indigenous herbivores and diseases to keep an introduced plant in check when it becomes invasive on other continents. Teasel is, as mentioned, a striking plant, sometimes used in dry flower arrangements. Invasive is another way of saying "too much of a good thing." It would be interesting to see how teasel behaves in the English landscape, beyond the confines of a 10 X 20 butterfly garden.Towards the end of the tour, our hosts in Nottingham, owners of a wonderful jazz club called Peggy's Skylight, put us up at their homes. The foliage in front of one of the houses along the street was decidedly American, with pampas grass and Virginia creeper.

There's a wonderful post about Virginia creeper by a woman in London who describes herself this way: "Bug Woman is a slightly scruffy middle-aged woman who enjoys nothing more than finding a large spider in the bathroom."

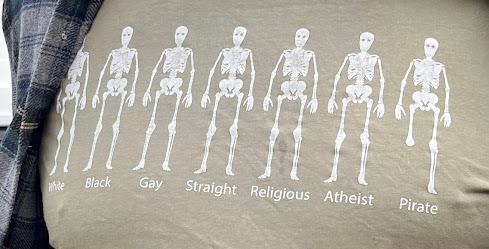

We were fortunate in Nottingham to have an instantly likable host named Lex, a geographer with a liking for pirates and educational t-shirts.

Their dog is a small version of a pure bred fox hound, the runt of the litter. The sort that hunts foxes, Lex explained, are much larger and specially bred. He described the tradition of fox hunting historically as more a form of warfare than sport--a means by which the upper class could demonstrate dominion over the lands populated by the tenant farmers. Fox hunting became logistically difficult as the landscape became more broken up into smallholder parcels whose owners were less willing to go along with the periodic invasion.

While we found Robin Hood hanging out next to Nottingham Castle, built over ancient sandstone caves, he'd now have to drive an hour north to reach what remains of Sherwood Forest. There was no time for that, even though it looks like there's an amazingly old oak up there called the Major Oak.

We didn't see any fairs in Scarborough, but we did go, and did play for a thousand people at the jazz festival there. They called our music "joy jazz"--a new genre. Half the joy was in the music. The other half was in getting to see England and meet some of its people.

There was a very scary guard dog, fortunately leashed.

And a guard bird kept an eye on us. People underestimate guard birds at their peril.

The garden deals with the death of trees in an interesting way. People tend to eliminate all signs of death from their gardens, but our hosts see demise as an opportunity. What's this?, you might ask.

I did ask, and was told that it's a thumb. That's a very positive thing to do with a dead tree trunk.

And that split trunk in the distance, instead of cutting it down,

they added a rope and called it a sling-shot.

If you've been steeped in the American ethic that trees should be allowed to grow naturally, the European treatment of trees can seem at first brutal. This eucalyptus, native to Australia, is lucky to have any limbs. Radical pruning is a means of controlling size, and is reminiscent of how grape vines are pruned back each year to not much more than a post sticking out of the ground. New growth sprouts from the tips. Pollarding is a fascinating technique with a long history, and some examples, intentional or not, can be found in Princeton.

"... a diverse mosaic of habitats: native broadleaf woodland of oak, birch, rowan, and hazel; areas of mature and younger conifer; fern-clad hollows; and patches of heathland where the heather, gorse, and purple moor-grass harbour a host of wildlife."

"Fernclad hollows? Heather, gorse, purple moor-grass? If I had read the sign then and there, I would have launched myself up the trail for a closer look. Instead I took a photo of the sign, to ostensibly read later, and returned to the Sandstone House, still carrying the misconception that heather only grows further north, up towards Scotland. Rowan turns out to be the European equivalent of our mountain ash. Gorse looks a bit like a shrub called Scotch broom, with similarly bright yellow leguminous flowers. Both were introduced to the western U.S. and became invasive. It would have been good to see how gorse grows in its native habitat of Britain. The sign also says that Hargate Forest has its own invasive species, rhododendron, which is being removed.

One big surprise was the presence of palm trees in southern Great Britain. The photo below was taken in Torquay (pronounced tor-KEY, home of Faulty Towers) where our band did a workshop at a boy's grammar school. A grammar school, I learned, doesn't refer to teaching grammar but to the need to test to get in. Palm trees, yuccas, Bird of Paradise--the flora along the south coast was more reminiscent of Pasadena, CA than my preconception of a uniformly cold, damp England.

A little ways north, the climate still looked to be on the mild side, with fuchsia shrubs blooming in a garden designed for butterflies. It was at the Bristol Grammar School, reminiscent of Hogwarts, with uniformed students and a grand paneled dining hall.

In a big blackbox theater, we performed our original music, then brought the students down to learn how to play a street samba rhythm. It is tremendously satisfying to perform for a sea of bright young faces, who listened well and gave back as much energy as we gave them. Most jazz musicians, leaving the gig, would not have noticed the teasel growing in the little butterfly garden that was trying mightily to do its part to counter 50 years of decline in butterflies and moths in Great Britain. Apparently native to England, teasel is a plant with a striking form that unfortunately has become highly invasive in the midwestern U.S., forming thick stands along highways. It probably will become problematic in NJ over time. Typically there's a lack of indigenous herbivores and diseases to keep an introduced plant in check when it becomes invasive on other continents. Teasel is, as mentioned, a striking plant, sometimes used in dry flower arrangements. Invasive is another way of saying "too much of a good thing." It would be interesting to see how teasel behaves in the English landscape, beyond the confines of a 10 X 20 butterfly garden.

The wannabe urban planner in me would like to take a moment to heap praise upon shallow setbacks, which I will pretend is a botanical term for locating homes close to the street. The small front yard thus created is a manageable space for having a small garden. Princeton has some neighborhoods with these smaller setbacks, but where homes are placed far from the street, not only is it less likely one will get to know one's neighbor, but the vast front yard thus created is also too big for most people to garden. The solution most homeowners gravitate towards is a boring, sterile expanse of mowed lawn. In England, I was glad for the feeling of embrace the narrow streets and their close-in buildings create.

There's a wonderful post about Virginia creeper by a woman in London who describes herself this way: "Bug Woman is a slightly scruffy middle-aged woman who enjoys nothing more than finding a large spider in the bathroom."

The blogger's description of self begs the question: Are Brits more comfortable than Americans with self-deprecation? In downtown Nottingham, we saw the Ugly Bread Bakery,

which was just up the street from the Fatface department store. Do words get upcycled in England, to turn a negative into a positive? Though people were not above occasional complaint, we picked up on considerable positive energy, with the word "brilliant" being sprinkled liberally upon various things and actions, the way we might use "awesome."

which was just up the street from the Fatface department store. Do words get upcycled in England, to turn a negative into a positive? Though people were not above occasional complaint, we picked up on considerable positive energy, with the word "brilliant" being sprinkled liberally upon various things and actions, the way we might use "awesome."

One plant doing very well in England is English ivy, which looks to be a bonafide native. Vines typically bloom only when they climb something, which is why you never see English ivy, Virginia creeper, or poison ivy blooming when they are only spreading across the ground.

Along with the loss of wildlife, there's also the mourning of the attrition of hedgerows in the countryside. Apparently a lot were removed after WWII, when farming shifted towards maximum production and the hedgerows were standing in the way of expanding fields. Our pianist for the week, Adam Biggs, lives in Bath and described to me how hedgerows are not so much planted as "laid". There's a whole technique to creating and maintaining hedgerows, which are promoted as important habitat for wildlife.

A closer look reveals important anatomical differences between various strains of humanity.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)