One of our hosts, in Tunbridge Wells, has a delightful garden. The city is located in Kent, which is a county south of London. England as a country has no states, but rather lots of counties, like Hampshire, Yorkshire, and Devon, which seems to have lost its shire. Homes have addresses in England, but they are also sometimes given names. Our host lives in the Sandstone House. Are all english gardens like this? I'd be fine with it if so. Sheep graze peacefully in the front yard. Had never seen baby sheep grazing before. They're doing a great job.

Pink flamingoes are an indicator species for quirky habitat. Real flamingoes can be found in Africa and America. I once saw flocks of them at watering holes at the base of the Andes in the Patagonian desert in Argentina. Plastic pink flamingoes (Phoenicopterus plasticus) are a northern species, reportedly native to Massachusetts.

The nylon strings draped over the front yard water feature looked at first like a sculpture, but may also be an elegant deterrent of whatever local water bird might be tempted to fly in and gobble up the fish.

There was a very scary guard dog, fortunately leashed.

And a guard bird kept an eye on us. People underestimate guard birds at their peril.

There was a sheep patrolling the deck, looking like a character out of Wallace and Gromit. Very high security.

The garden deals with the death of trees in an interesting way. People tend to eliminate all signs of death from their gardens, but our hosts see demise as an opportunity. What's this?, you might ask.

I did ask, and was told that it's a thumb. That's a very positive thing to do with a dead tree trunk.

And that split trunk in the distance, instead of cutting it down,

they added a rope and called it a sling-shot.

If you've been steeped in the American ethic that trees should be allowed to grow naturally, the European treatment of trees can seem at first brutal. This eucalyptus, native to Australia, is lucky to have any limbs. Radical pruning is a means of controlling size, and is reminiscent of how grape vines are pruned back each year to not much more than a post sticking out of the ground. New growth sprouts from the tips. Pollarding is a fascinating technique with a long history, and some examples, intentional or not, can be found in Princeton.

Even more extreme pruning leaves just the trunk, as can be seen in this photo taken on the fly. It would be interesting to see how the trees respond to such extreme treatment.

There was a forest nearby that I didn't have time to explore, but the description sounds appealing.

Most jazz musicians, leaving the gig, would not have noticed the teasel growing in the little butterfly garden that was trying mightily to do its part to counter 50 years of decline in butterflies and moths in Great Britain. Apparently native to England, teasel is a plant with a striking form that unfortunately has become highly invasive in the midwestern U.S., forming thick stands along highways. It probably will become problematic in NJ over time. Typically there's a lack of indigenous herbivores and diseases to keep an introduced plant in check when it becomes invasive on other continents. Teasel is, as mentioned, a striking plant, sometimes used in dry flower arrangements. Invasive is another way of saying "too much of a good thing." It would be interesting to see how teasel behaves in the English landscape, beyond the confines of a 10 X 20 butterfly garden.Towards the end of the tour, our hosts in Nottingham, owners of a wonderful jazz club called Peggy's Skylight, put us up at their homes. The foliage in front of one of the houses along the street was decidedly American, with pampas grass and Virginia creeper.

There's a wonderful post about Virginia creeper by a woman in London who describes herself this way: "Bug Woman is a slightly scruffy middle-aged woman who enjoys nothing more than finding a large spider in the bathroom."

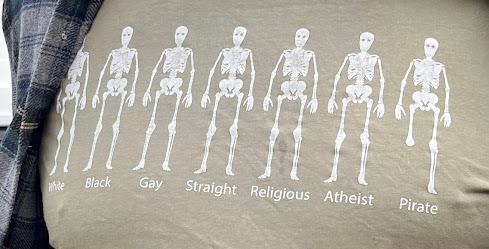

We were fortunate in Nottingham to have an instantly likable host named Lex, a geographer with a liking for pirates and educational t-shirts.

Their dog is a small version of a pure bred fox hound, the runt of the litter. The sort that hunts foxes, Lex explained, are much larger and specially bred. He described the tradition of fox hunting historically as more a form of warfare than sport--a means by which the upper class could demonstrate dominion over the lands populated by the tenant farmers. Fox hunting became logistically difficult as the landscape became more broken up into smallholder parcels whose owners were less willing to go along with the periodic invasion.

While we found Robin Hood hanging out next to Nottingham Castle, built over ancient sandstone caves, he'd now have to drive an hour north to reach what remains of Sherwood Forest. There was no time for that, even though it looks like there's an amazingly old oak up there called the Major Oak.

We didn't see any fairs in Scarborough, but we did go, and did play for a thousand people at the jazz festival there. They called our music "joy jazz"--a new genre. Half the joy was in the music. The other half was in getting to see England and meet some of its people.

There was a very scary guard dog, fortunately leashed.

And a guard bird kept an eye on us. People underestimate guard birds at their peril.

The garden deals with the death of trees in an interesting way. People tend to eliminate all signs of death from their gardens, but our hosts see demise as an opportunity. What's this?, you might ask.

I did ask, and was told that it's a thumb. That's a very positive thing to do with a dead tree trunk.

And that split trunk in the distance, instead of cutting it down,

they added a rope and called it a sling-shot.

If you've been steeped in the American ethic that trees should be allowed to grow naturally, the European treatment of trees can seem at first brutal. This eucalyptus, native to Australia, is lucky to have any limbs. Radical pruning is a means of controlling size, and is reminiscent of how grape vines are pruned back each year to not much more than a post sticking out of the ground. New growth sprouts from the tips. Pollarding is a fascinating technique with a long history, and some examples, intentional or not, can be found in Princeton.

"... a diverse mosaic of habitats: native broadleaf woodland of oak, birch, rowan, and hazel; areas of mature and younger conifer; fern-clad hollows; and patches of heathland where the heather, gorse, and purple moor-grass harbour a host of wildlife."

"Fernclad hollows? Heather, gorse, purple moor-grass? If I had read the sign then and there, I would have launched myself up the trail for a closer look. Instead I took a photo of the sign, to ostensibly read later, and returned to the Sandstone House, still carrying the misconception that heather only grows further north, up towards Scotland. Rowan turns out to be the European equivalent of our mountain ash. Gorse looks a bit like a shrub called Scotch broom, with similarly bright yellow leguminous flowers. Both were introduced to the western U.S. and became invasive. It would have been good to see how gorse grows in its native habitat of Britain. The sign also says that Hargate Forest has its own invasive species, rhododendron, which is being removed.

One big surprise was the presence of palm trees in southern Great Britain. The photo below was taken in Torquay (pronounced tor-KEY, home of Faulty Towers) where our band did a workshop at a boy's grammar school. A grammar school, I learned, doesn't refer to teaching grammar but to the need to test to get in. Palm trees, yuccas, Bird of Paradise--the flora along the south coast was more reminiscent of Pasadena, CA than my preconception of a uniformly cold, damp England.

A little ways north, the climate still looked to be on the mild side, with fuchsia shrubs blooming in a garden designed for butterflies. It was at the Bristol Grammar School, reminiscent of Hogwarts, with uniformed students and a grand paneled dining hall.

In a big blackbox theater, we performed our original music, then brought the students down to learn how to play a street samba rhythm. It is tremendously satisfying to perform for a sea of bright young faces, who listened well and gave back as much energy as we gave them. Most jazz musicians, leaving the gig, would not have noticed the teasel growing in the little butterfly garden that was trying mightily to do its part to counter 50 years of decline in butterflies and moths in Great Britain. Apparently native to England, teasel is a plant with a striking form that unfortunately has become highly invasive in the midwestern U.S., forming thick stands along highways. It probably will become problematic in NJ over time. Typically there's a lack of indigenous herbivores and diseases to keep an introduced plant in check when it becomes invasive on other continents. Teasel is, as mentioned, a striking plant, sometimes used in dry flower arrangements. Invasive is another way of saying "too much of a good thing." It would be interesting to see how teasel behaves in the English landscape, beyond the confines of a 10 X 20 butterfly garden.

The wannabe urban planner in me would like to take a moment to heap praise upon shallow setbacks, which I will pretend is a botanical term for locating homes close to the street. The small front yard thus created is a manageable space for having a small garden. Princeton has some neighborhoods with these smaller setbacks, but where homes are placed far from the street, not only is it less likely one will get to know one's neighbor, but the vast front yard thus created is also too big for most people to garden. The solution most homeowners gravitate towards is a boring, sterile expanse of mowed lawn. In England, I was glad for the feeling of embrace the narrow streets and their close-in buildings create.

There's a wonderful post about Virginia creeper by a woman in London who describes herself this way: "Bug Woman is a slightly scruffy middle-aged woman who enjoys nothing more than finding a large spider in the bathroom."

The blogger's description of self begs the question: Are Brits more comfortable than Americans with self-deprecation? In downtown Nottingham, we saw the Ugly Bread Bakery,

which was just up the street from the Fatface department store. Do words get upcycled in England, to turn a negative into a positive? Though people were not above occasional complaint, we picked up on considerable positive energy, with the word "brilliant" being sprinkled liberally upon various things and actions, the way we might use "awesome."

which was just up the street from the Fatface department store. Do words get upcycled in England, to turn a negative into a positive? Though people were not above occasional complaint, we picked up on considerable positive energy, with the word "brilliant" being sprinkled liberally upon various things and actions, the way we might use "awesome."

One plant doing very well in England is English ivy, which looks to be a bonafide native. Vines typically bloom only when they climb something, which is why you never see English ivy, Virginia creeper, or poison ivy blooming when they are only spreading across the ground.

Along with the loss of wildlife, there's also the mourning of the attrition of hedgerows in the countryside. Apparently a lot were removed after WWII, when farming shifted towards maximum production and the hedgerows were standing in the way of expanding fields. Our pianist for the week, Adam Biggs, lives in Bath and described to me how hedgerows are not so much planted as "laid". There's a whole technique to creating and maintaining hedgerows, which are promoted as important habitat for wildlife.

A closer look reveals important anatomical differences between various strains of humanity.

No comments:

Post a Comment