News from the preserves, parks and backyards of Princeton, NJ. The website aims to acquaint Princetonians with our shared natural heritage and the benefits of restoring native diversity and beauty to the many preserved lands in and around Princeton.

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Princeton's Nowhere Land Might Have a Future

Monday, January 09, 2023

What Privet is This? Border Privet in Princeton

Sunday, January 08, 2023

Rogers Refuge Featured in the Princeton Echo

For the past two years, Princeton Echo has started the new year with a feature article about a local nature preserve. Last year, it was Herrontown Woods, and this year, Rebekah Shroeder wrote an extended portrait of the birding mecca Rogers Refuge and the volunteers who have cared for it since the 1960s.

The Charles H. Rogers Wildlife Refuge is a hidden gem, a covert part of Princeton's beauty and ecological richness, accessed down an often passed but seldom seen gravel road called West Drive. Climb the observation tower just in from the parking lot and you will see a most unlikely vista for Princeton--a grand marsh.

Friday, January 06, 2023

Conspicuous Earth Hugging By Trees

Root flare is a sign of health in trees, but I'd never seen the likes of this. I'm calling it a kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra) after encountering this charming video that describes its buttressed base and the fluffy seeds that used to provide stuffing for life vests.

The extravagant buttressing is reminiscent of the fins of a rocket that in this case can reach more than 200 feet tall, vaulting above the rainforest canopy. With seedpods packed with useful fiber, it's not surprising that the kapok is in the same plant family as cotton--the Malvaceae, also known as the mallow family.

The ombu, a native to the Argentine pampas that goes by the latin name Phytolacca dioica, develops a conspicuously bloated base that with time can become convenient for sitting. If you haven't seen one, just imagine a 50 foot high pokeweed--our local Phytolacca americana with very similar leaves, flowers, and berries.

Tuesday, January 03, 2023

Strangler Figs: Airborne Roots and Flying Buttresses

How silly we are, these extraordinary trees seem to say, to think that trees should start life on the ground, have only one trunk, make their flowers seen and keep their roots tidily hidden.

while others drape themselves over walls,

or probe the local infrastructure.

Monday, December 26, 2022

Names I Remember, Names I Forget

One ongoing self-observation that I've had through a life of nature observation is that there are some plant names that resiliently spring to mind, and others that remain persistently unretrievable no matter how many times I learn and relearn them. For example, the latin names Gleditsia triacanthos and Robinia pseudoacacia look esoteric and intimidating, and yet for some reason I can summon them instantly. They refer to honey locust and black locust, respectfully, though I don't knowingly have any deeper interest in or respect or affection for these two trees than any others. Well, that's not completely true. I love black locust because it resists rot and burns clean. It can lie on the ground for years and still make great firewood. And a thornless version of honey locust makes a wonderful shade tree in public squares, its tiny leaflets melting back into the landscape in the fall. But I love other trees for their traits just as much. Gleditsia and Robinia, then, are two trees among many in my mind, and yet their names remain buoyantly floating above the others, at the top of the heap and the tip of the tongue.

At the other extreme lies fennel, a delicious, fragrant vegetable that grows gloriously. A friend made a casserole with fennel and leeks wrapped with prosciutto, the cheese on top baked to a golden brown. It was to die for, and yet the word "fennel" still dropped down into the cerebral abyss, dredged back up just now only by once again googling "plant that tastes like licorice." Similarly, there's a kind of lightbulb whose name I can never remember. The others come dependably and quickly to mind: florescent, incandescent, LED, mercury vapor. But the other one ... I think it starts with an "a" but I could be wrong. That's right. I was wrong, again. Had to google. It starts with an "h," as in "halogen."

What's the difference here? Gleditsia and Robinia make a merry, musical pair, both with impactful accents on the second syllable: gle-DIT-see-a and ro-BIN-ee-a. Fennel and halogen are less musical, with the accent landing heavily on the first syllable, like tunnel, or funnel, or allergen, or estrogen, or pathogen. But "merry" and "musical" also have the accent at the beginning, so maybe it's that the words "fennel" and "halogen" get less merry and musical after the first syllable, with consonants that are soft and easily swallowed up. I often think about this when comparing the names "Veblen" and "Einstein." Einstein has a memorably sonorous name that can be drawn out deliciously when spoken, like a double exclamation point, fitting for his matchless legacy. Veblen, on the other hand, whose quietly extraordinary career flew under most people's radar, then was long left for forgotten, has a name with soft consonants and indistinct vowels that are all too easy to mumble.

There's a belief that forgetting someone's name reflects a negative view of that person, but I find I can just as easily forget the name of someone I have just met and like. Next time that happens I'll pay attention to the sound of the name itself. It's fun to explore these things, and maybe the act of writing this will create an inner web of meaning to catch "fennel" and "halogen" before they once again drop into the abyss.

Thursday, December 15, 2022

The Invasive Species of the Month Club

Privet was the main focus of this past Sunday's Invasive Species of the Month Club. The weather was cold and damp, with rain threatening, but surprisingly it was one of our most satisfying sessions. The little boy in the lime green dinosaur coat was totally into it, and we managed to clear a whole section of the valley of a dense tangle of invasives. There's enough space in the tree canopy to power native wildflowers and shrubs there, once the invasive shrubs and vines have been subdued. That's the goal, but the process of group effort and gaining increasing confidence and familiarity out in nature have their own satisfactions.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

The Blob That Swallowed Our Nature Walk

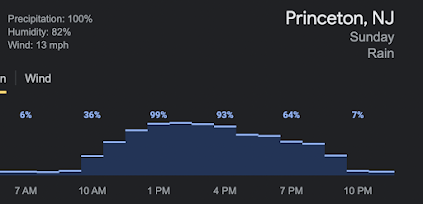

I'd been watching the weather for Sunday all week. It was almost comic how a big pile of predicted rain sat centered over the exact timeframe for the scheduled nature walk at Herrontown Woods--a mountain of rain rising conspicuously, incongruously, out of a prairie of sunny weather stretching into the distance on either side.

Astute readers will note a distinct resemblance between the blob of rain that swallowed our nature walk and the drawing of a boa constrictor that had swallowed an elephant in The Little Prince.

Finally, we bailed, and rescheduled the walk for a week later.

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

Nature Walk at Herrontown Woods, Sunday, Nov. 27, 1-3pm

A nature walk is planned for this Thanksgiving weekend, on Sunday, Nov. 27, from 1-3pm. If the weather looks iffy, check the events page of the HerrontownWoods.org website for an update.

We'll meet at the Herrontown Woods parking lot at 600 Snowden Lane, across Snowden from the Smoyer Park entrance. Sturdy shoes are a good idea. Maps at this link.

The photo is of a pokeweed that came late to the fall color party.

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Solarizing a Princeton High School Detention Basin

Earlier this fall, I was passing by Princeton High School on Walnut Street when I saw something I'd never seen before:

a whole field covered with plastic. The field, next to the tennis courts and a parking lot, is actually a stormwater detention basin that the school wants to replant as native meadow. But before planting, they need to kill the existing turfgrass.This PHS environmental science teacher is one of several using this detention basin as well as the ecolab to teach about stormwater issues and habitats.

Friday, November 11, 2022

What's Eating Local Viburnums?

Each time I see a native arrowwood Viburnum growing in the woods, I take a closer look. There's a viburnum leaf beetle--a nonnative species introduced from Europe--that showed up in Princeton about a decade ago. On a visit to Pittsburgh years back, I saw native Viburnums totally skeletonized by the insect, and worried about the fate of our own Viburnums in NJ.

I've posted about this insect pest in the past. Suffice it here to say that among the various species of Viburnum in NJ, the arrowwood Viburnum (V. dentatum) is the most vulnerable. The nightmare scenario would be for the leaf beetle to defoliate all arrowwood Viburnums, then move on to decimate the next most vulnerable species.Nature at the Princeton Battlefield

(Thanks to those who commented. Scroll down for an update.)

The sign tells the story of the white oak and General Mercer. What I've come to look at, though, is not the highly symbolic tree but a thin sliver of golden brown in the distance.

Beyond the lawn, towards the back of the Battlefield, is a meadow that is mowed once a year. For some reason they mowed the edge of it this fall but have left the rest, perhaps as winter cover for wildlife.

Taking a closer look, I'm surprised to see that, among the blackberries and prairie grasses, goldenrods and asters, are myriad sassafras sprouts, most of them bright orange this time of year. The meadow is a giant clone of sassafras--one root system with ten thousand heads. Can't say I've ever seen that before.