There's a lot of gratitude being expressed towards trees these days. The gratitude tends to be towards trees in general, but this fall, I'm especially grateful for three trees in particular.

News from the preserves, parks and backyards of Princeton, NJ. The website aims to acquaint Princetonians with our shared natural heritage and the benefits of restoring native diversity and beauty to the many preserved lands in and around Princeton.

Friday, October 27, 2023

Update on Native Butternuts and Chestnuts in Princeton

Monday, March 27, 2023

Coyote Spotted at Princeton Battlefield

A coyote was spotted at Princeton Battlefield this past Friday, March 24.

Thanks to David Padulo for sending around this photo of the beautiful animal. At the time, David (hopefully not the coyote), was on his way to Port Mercer "to check off a Mercer County Life bird (Tundra Swan)," and so happened to have his camera. Port Mercer, for those like me who would assume there aren't any ports near Princeton, turns out to be just a couple miles upstream: the historic settlement where Quaker Road crosses the canal. According to David, the tundra swan was off track, a half hour away from where they are more typically seen, at Assunpink in Monmouth.Friday, November 11, 2022

Nature at the Princeton Battlefield

(Thanks to those who commented. Scroll down for an update.)

The sign tells the story of the white oak and General Mercer. What I've come to look at, though, is not the highly symbolic tree but a thin sliver of golden brown in the distance.

Beyond the lawn, towards the back of the Battlefield, is a meadow that is mowed once a year. For some reason they mowed the edge of it this fall but have left the rest, perhaps as winter cover for wildlife.

Taking a closer look, I'm surprised to see that, among the blackberries and prairie grasses, goldenrods and asters, are myriad sassafras sprouts, most of them bright orange this time of year. The meadow is a giant clone of sassafras--one root system with ten thousand heads. Can't say I've ever seen that before.

Friday, October 21, 2022

The Emerald Ash Borer Quietly Changes Princeton's Skyline

clear fallen Ash trees from the Red Trail. It’s really heartbreaking."

In this section of trunk, where the bark has fallen away, you can see how the Emerald Ash Borer larvae consume the tree's cambium. Like the earth's total dependence on a thin surrounding layer of atmosphere (which of course our machines' invisible emissions are radically altering), a tree's vascular system depends on a thin layer of tissue surrounding the trunk, just below the bark. Lacking any evolved defense against the introduced ash borers, the native ash trees quickly become girdled and die.

I would speculate that, once the native and introduced parasitic wasps become widespread, they in combination with woodpeckers could allow ash trees to persist in Princeton, though perhaps few would grow to maturity unless regularly treated with systemic pesticide.Carolyn Edelman, a poet and nature enthusiast, recently posted a quote of Adlai Stevenson, II, dating back to a speech he gave in 1952. Its sentiment is part of a vein of American thought that views love of the American landscape as deeply connected to the love of freedom. For me, it is not coincidence that we live in a time when both nature and democracy are being undermined. Read the quote through today's filter of gender equality and inclusion to find its relevance.

It was always accounted a virtue in a man to love his country. With us it is now something more than a virtue. It is a necessity. When an American says that he loves his country, he means not only that he loves the New England hills, the prairies glistening in the sun, the wide and rising plains, the great mountains, and the sea. He means that he loves an inner air, an inner light in which freedom lives and in which a man can draw the breath of self-respect. Men who have offered their lives for their country know that patriotism is not the fear of something; it is the love of something.A great tree species passes from the landscape, but the love remains, and in that love reside both grief and possibilities.

Friday, February 25, 2022

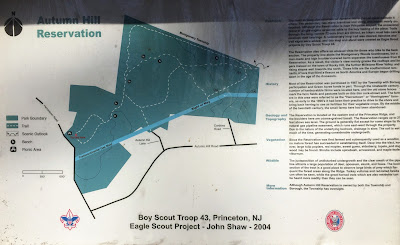

Autumn Hill Reservation--Past and Present

An early presence out Autumn Hill way, east and south of the present day preserve, was Camp Tamarack, the 30 acre Girls Scout camping ground that dates back to 1948. Remnants of a foundation and outhouse can still be found by following an old abandoned trail down from the end of Autumn Hill Road--a deadend street that was built as part of a subdivision in 1956. Girlscouts would camp there on weekends, sometimes combining the camping with sailing on Carnegie Lake.

A 1966 article announces obliquely that Township Open Space Commission "has obtained use of the Autumn Hill Reservation," and in 1969 the preserve is described as "new", with a parking lot but trails not fully laid out. The sign on the kiosk says that most of the land was acquired in 1967, with funding from township, borough, and the state's Green Acres fund."Autumn Hill" is the newest of the Open Space lands in terms of a good loop trail you can follow. The trail was built by YMCA Rangers. Picnicking is invited in Autumn Hill, too, and later this spring, there will be picnic tables. Right now, there is drinking water and you can bring your own picnic lunch.

In 1984, a big battle raged to fend off a proposed road, Route 92, that would have destroyed large swaths of open space, including part of Autumn Hill Reservation.

Fast forward to 1995, when local arborist Bob Wells proposed to officially adopt Autumn Hill Reservation. Bob was renting the nearby Veblen House from the county at the time.

Committee accepted an offer from Robert Wells that his tree and landscape firm adopt the park at Autumn Hill Reservation off Herrontown Road. Mr. Wells, chair of the Township Shade Tree commission and a Herrontown Road resident, has performed extensive tree and trail maintenance in the park on a volunteer basis over the past several years. He also supervised the creation of one trail that was an Eagle Scout project. He now proposes to reestablish the picnic area off the parking lot, rebuild the frost-free water spigot and erect an additional foot-bridge. He also plans to install tree identification signs and a trail map and do general maintenance to the trails and path system. In accepting the offer, Township Committee signaled it was launching an "adopt-a-park" program to enable other businesses and individuals to volunteer their services for Township parks.

There's been an increase in interest in Autumn Hill recently, particularly from people living on the other side of the ridge in Montgomery who would like a better connection to the preserve from that side. Though we've done some small reroutes of trails onto drier ground, there is more we hope to do this year, laying boardwalk and shifting some trails to drier ground.

Winter is a good time to look for better routes for trails. Andrew Thornton and I recently noticed a potential improvement that would run along the edge of a stone wall currently hidden by densely growing honeysuckle, winged euonymus, Asian photinia, barberry, and privet. The nonnative shrubs flourish because deer and other wildlife don't eat them. I made some headway one afternoon, cutting through the thicket with loppers and a saw, constantly dodging the thorns of multiflora rose. Who's to say what the dominant motivation is. Love of a good trail? A desire to leave the world a better place than one found it? The satisfaction of work where progress is clear? A stewardship ethic engrained from youth? One strong motivation is the standing water that makes the current trail route nearly impassable this time of year. Rerouting the trail along higher ground, next to a rock wall, will give us a trail that's both drier and more interesting. Win-wins help to spur one on.

Looking back through time, it can be heartening to see how people in the past stepped up to take care of public lands, just as we do now. It can also be unsettling, though, to see that periods of care do not always last, and can be followed by periods when trails slowly return to thicket, awaiting the next inspired steward to come along. What makes us think current efforts will be any different? That "adopt a park" program started in 1995 was well-intentioned, but the groups that stuck with it after the first flush of interest are few.

During my Durham days, I started a program in which interested neighbors could adopt 20 feet of a paved bike trail that went through a nature preserve. The aim was for each family or individual to gain a sense of ownership of a small section of trailside vegetation, planting native plants and weeding occasionally, until the entire length of trail would be a verdant showcase for sedges, rushes and wildflowers. There was early interest, but most people didn't stick with it. What I learned is how few people are hardwired to garden, and even fewer hardwired to garden in a public space.

Back in 1973, recycling was in a similar "heroic" stage, with a few dedicated volunteers trying to divert newspapers, bottles and tin cans from the waste stream. Like many municipalities across the country, Princeton was grappling with how to "get recycling out of the garage and volunteer stage and into the solid waste volume reduction and resource recovery stage on a long term regional basis." I was part of that 70's era volunteer recycling stage as well, standing on a flatbed truck as we drove through a neighborhood, stacking homeowners' bundled newspapers on the truck, and crushing glass--brown, green, and clear--in oil drums, as part of a pilot curbside recycling program in Ann Arbor, MI. Curbside recycling ultimately became institutionalized, but stewardship of open space is still in the "catch as catch can" volunteer stage.

Postscript: There's another question that lingers from this dive into history: Where is that water spigot from which drinking water once flowed in Autumn Hill Reservation?

PostPostscript: Didn't take long to find the old water spigot, just a few feet away from the parking lot.Thursday, December 30, 2021

Native Chestnuts in Princeton--the Next Generation

Many of us have lived our whole lives without seeing a mature native American chestnut tree. An excellent NY Times Magazine article described it as a true gift of nature, the perfect tree, growing straight and tall, with rot-resistant wood, and bearing nuts that were easily gathered and eaten, sustaining wildlife and people alike. My first encounter with the American chestnut was the sight of their fallen trunks in a Massachusetts forest, 70 years after the fungus that causes chestnut blight was discovered in NY city in 1904. The massive trunks I saw, lying on a slope in the shade of young white pine, were among the billions that the accidentally imported fungus would ultimately kill in the U.S. Since the roots survive the fungus, there was still a living community of underground chestnut trees beneath our feet in that Massachusetts forest. One of the roots had sent up a sprout about twenty feet tall--promising, one would like to think, but its slim trunk was already ringed by the fungus, its fate sealed before it could bear nuts.

One of the projects I'm involved in is reintroducing native chestnuts to Princeton. The initiative began in 2009 with an email from Bill Sachs, a Princetonian with considerable expertise when it comes to nut-bearing trees. Bill reported that Sandra Anagnostakis, "one of (if not the) world’s leading experts on the pathology of American chestnut," had agreed to supply us with disease-resistant, hybrid American chestnut trees. Sandra's efforts to breed resistant native chestnuts at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station over many decades was apparently unconnected to the American Chestnut Foundation. The trees were 15/16th native, and Bill with occasional help from me and others proceeded to plant them at the Princeton Battlefield, Harrison Street Park, the Textile Research Institute, Mountain Lakes and Herrontown Woods.

Some fared better than others. Many, despite having been bred for resistance, nonetheless struggled with the blight that had laid the mighty tree low a century ago. This fall, however, paralleling our work to bring back native butternuts, one of the chestnut trees has borne fertile seeds.

Bill made repeat visits to the tree to collect the nuts as they ripened. The deer likely got many, but he managed to gather quite a few, some of which he encouraged me to cold stratify. Stratification has always been an intimidating concept for me, suggesting sophisticated manipulation to get a seed to germinate, but in this case it turned out to be not much more than stuffing some seeds in a bag of moist peat moss and leaving it in the back of the refrigerator for awhile.Sunday, September 19, 2021

Mile-a-Minute Spreading into Princeton

One of the more noxious invasive plants that has been spreading across NJ is Mile-a-Minute. It's a prickly vine that, though an annual that must grow back from seed each spring, grows so fast that it can cover large areas of roadsides and field edges. Over the past several years, I've been knocking out small infestations at the Princeton Battlefield and near Rogers Refuge, but this year I'm finding new patches springing up around town.

Then, driving my daughter to MarketFair along Canal Pointe Blvd a week ago, I saw a massive infestation that surely is a major source of the seeds that birds are then spreading across Princeton.Saturday, November 28, 2020

The Second Forest of Institute Woods

Here, viewed from the Streicker Bridge over Washington Road a week or two ago, are Norway Maples pushing up into the canopy of mature native oaks, beech, and blackgum, some of which are two centuries old.

Bamboo at the Princeton Battlefield, bordering the Institute lands, offers another variation on the theme.

Here the pink of the winged euonymus mingles with the still green multiflora rose. Linden viburnum has its own distinctive fall color,

the Taplins who led the way,

the coordination of governmental, institutional, and nonprofit entities that in NJ has been so effective in saving land.

Here, on this plaque, would have been a good place to mention the Lenape Indians as early occupants and stewards. A whole additional plaque could be dedicated to telling of Oswald Veblen's role as primary instigator of acquisition. As partially told on the IAS website, and more fully told by George Dyson in a talk at DR Greenway, Veblen convinced the early Institute leadership to acquire the land, then did the legwork necessary to bring all the parcels together. Over ten years, beginning in 1936, Veblen laid the foundation for open space in Princeton, with the acquisition not only of the Institute lands but also the 100 acres on the east side of Princeton that he and his wife Elizabeth later donated as Princeton's and Mercer County's first nature preserve, Herrontown Woods.

Saturday, August 01, 2020

Mile-a-Minute Vine in Princeton

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

Invasive Mile-a-Minute Spreading at Princeton Battlefield

Ever find yourself caring deeply about something the rest of the world ignores? We all pick our battles, and here's a really good one for the Friends of Princeton Battlefield and/or our governing institutions to pick.

Princeton has been graced in many ways of which it is not even aware, and one of those is the up-to-now absence of Mile-a-Minute, a thorny annual vine that grows up and over everything if allowed. Gardeners beware. This one's particularly nasty, and though it has gained a foothold in nearby areas, I've encountered it in only two locations in Princeton. One location is the Princeton Battlefield. The other is on the gravel road in to Rogers Refuge. Each year I pull it out, but by the time I remember to do it, a few of the vines' little blue berries have matured, so the infestation has been growing.

Obviously, my efforts are not enough. The town of Princeton has fortunately hired the NJ Invasive Species Strike Team in recent years to treat invasions by new species, but the Battlefield is state owned, and because of a lack of intervention it is now serving as a seed source that will affect all Princetonians, and not only for Mile-a-Minute.

Another issue at the Princeton Battlefield is the massive invasion by porcelainberry--a vine that rivals kudzu in its capacity to sprawl over anything and everything. Its overwhelming presence may seem to dwarf the problem with Mile-a-Minute, yet it can also be seen as proof that we really need to catch these invasions early, before they get out of control. Porcelainberry is not only at the Battlefield, but is also dominating large areas all along the Stonybrook in Princeton.

Here are the copious berries produced by porcelainberry vines as they smother the flowering dogwoods planted in 1976 for the nation's bicentennial. The berries turn pretty colors--blue, purple, pink, or white--thus the name, and the original appeal of the plant. But the plant has escaped the usual checks and balances that otherwise sustain balance in nature.

Birds eat the berries of porcelainberry and Mile-a-Minute, thus the concern that what's allowed to grow at the Battlefield will impact the rest of Princeton.

The Friends of the Battlefield group, by the way, has been doing a great job knocking out big stands of bamboo around the Clark House during its annual workday in April. Look in the distance in the photo and you'll see an open field, with only a small remnant of bamboo back near the woods.

But bamboo doesn't spread by seed, and so poses no threat beyond the Battlefield's borders. Volunteer sessions can slow down porcelainberry and Mile-a-Minute a bit, but for any lasting benefit, we need to get some professional intervention. Maybe the Friends of the Battlefield could apply for a grant.

In the meantime, be on the lookout for its distinctive triangular leaf, put on some gloves, and pull it out.